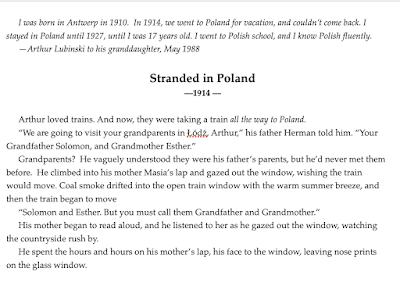

It might be reasonable to describe this project as perhaps the biggest, most expensive scrapbook page ever created. The map (printed in the late 1930s) wasn't especially expensive, but it's big (including the frame, it's 26" wide by 28" tall, 66cm x 71cm) and professional framing ain't cheap (and I even sprung for non-glare glass).

|

| Framed map. (Click to enlarge) |

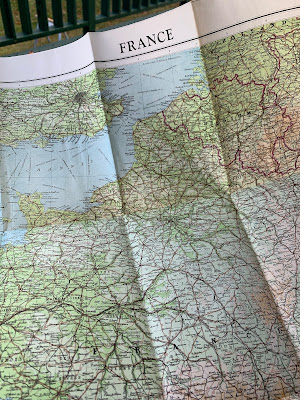

Maps of France aren't expensive. You can get excellent modern road maps off Amazon for a few dollars. But when I started researching my grandparent's lives during WWII, I realized that I needed a map that showed French and preferably Belgian roads and rails as they were during WWII.

My husband Chris is my resident map guy, and I don't know how he found it, but he stumbled across a book printed by the British Naval Intelligence back in 1942, called FRANCE: Volume 1 - Physical Geography. The book was actually restricted, not because it contained anything top secret, but because it contained everything about France's geography that one might need to, say, help the French Resistance units fight off Nazis, and it was all contained in one small, convenient book. It's no longer restricted, of course. Today you can find far more detailed information using Google Maps and Wikipedia.

But most importantly, it contained a pocket in the inside back cover with a vintage map that had been printed in the late 1930s. And he found a copy of the book at a used book store in England, and the proprietor verified the map was intact and in good shape. $25 including shipping from England, and 10 days later, I had it in my hands.

|

| Front cover |

|

| Title page |

|

| Pocket with intact map. |

|

| Map! (Note the creases) |

I bought a cheap poster frame big enough to hold the map, thinking I'd place sticker versions of arrows and pins to show where my grandparents were, and to show their movements.

But it looked awful. First, the poster frame wasn't stiff enough to hold the map flat between the clear plastic, and the particle board backing (which I covered with acid-free card stock to protect the vintage map), and I didn't have time to press the map flat for a few months between heavy objects - I needed it now. The book was in progress. So those creases were very evident, and it was hard to to follow the map in a continuous manner, because you had to tilt your head different ways when you went over the crease.

And the poster frame fit one dimension well (it was the right width) but was wildly too tall so there was this huge blank section above the map (remember how I said it wasn't sturdy enough to hold it flat? It also wan't really sturdy enough to hold it centered vertically in the frame). And I didn't want to use tape to hold it in place, because it was a vintage map. We must protect vintage maps, right?

I tried smoothing it, even (VERY CAREFULLY) ironing it, but that map had been folded for the better part of a century, and the creases were proving very stubborn, and resisted (pun intended!) all my efforts.

Another problem was that it didn't quite have the resolution I wanted - Ourches, France for example isn't even marked (town only has 250 people today, and had fewer than 100 people in the 1940s, but I could still stick a pin about where it is.

So I decided to have it professionally framed. I like maps, and I had a feeling that if I actually finished the book about my grandparents (end of January 2022, I finished the first draft, and I'm starting revisions soon), that I'd want to have the map as a permanent memento.

I had been thinking that someday, I'd return the map to the book. But ... those creases were a problem in a cheap frame, and they were going to be a problem in a professional frame, too. So (and this still makes me cringe a little) I had it dry mounted on foam core.

Yeah, no. That map is never going back into the book. I feel a little like I permanently damaged the map. But, it worked and it looks awesome. You can still see where the creases were if you look closely (and it gives it some character that I rather like), but it's laying flat now.

As soon as I got it home I pulled out the map dots I'd ordered weeks ago, but never stuck to the cheap frame. The map dots are super cool - they come in all different colors, and they are transparent, so you can still see the map through them. I also bought "pin" stickers shaped like the pins in Google Maps. I only dropped pins in locations my grandfather specifically mentioned. To replicate that below, I've turned the places that he specifically mentioned to the appropriate color.

Then, I went to town, sticking them to the glass:

- Orange dots: First escape to France in May 1940, from Brussels to Pas-de-Calais on the North Sea, in a taxicab of all things, and then several weeks later, back to Brussels after France surrendered. The route is entirely guesswork, though. I know they started in Brussels and ended in Pas-de-Calais, and stayed on a farm as a refugee for several weeks. I think they saw the North Sea, but the text isn't clear. When he said, "we arrived at Pas-de-Calais on the North Sea" did he mean that P-d-C is on the North Sea, (which it is - Dunkirk, Gravelines, and Calais are right there on the water, but there's plenty of that departmént which is not) or did he mean they arrived in P-d-C and were at the the North Sea? I took it to mean the latter, but the timing means they arrived when Dunkirk and Calais were a war zone. I just can't know where they were for sure. It's a little like mapping a route from ... Terre Haute to Missouri at the Mississippi River. So there is an orange Brussels pin, but no orange pin in northern France.

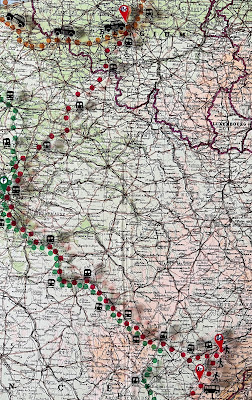

- Red dots: Second escape to France in the fall of 1941, from Brussels to Antibes, then back up to Valence. The entire northern half of the route is guesswork. Grandpa mentioned taking the train from Brussels as the starting point, to Besançon, but other than that, I've got nothing -- he didn't mention which train route at all, and there were many. Straight south through Luxembourg and Switzerland? Or through France, but extreme eastern France, with many stops? Or through the hub of Paris? So I chose to have them follow a couple of "escape lines" that resistance organizations used to get downed Allied airmen to safety. And ALL of the different escape lines passed through Paris on the train. It was also the fastest and most direct, with the fewest stops (and therefore checkpoints). So, Brussels - Paris - Dijon - Besançon by train. From Besançon they walked 35 miles (56 km) through Arbois, probably to Poligny, then took the bus to Lyon, then train down to Antibes. Then the train back up to the Valence area, where they stayed for the next 5 1/2 years.

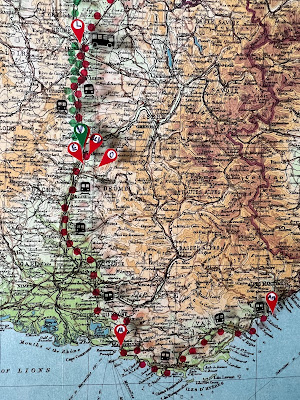

- Green dots: Immigration to the US in Jan-Feb 1947, from Valence to Paris, then Paris to Calais by train, then a ferry across the channel, then train to London. Then they took a plane from London to New York City.

It looked pretty great, but I really wanted to indicate modes of transportation, so I could find in an instant where certain things were. I imagined that I'd point to the map and say, "this is where they walked across the demarcation line, on foot."

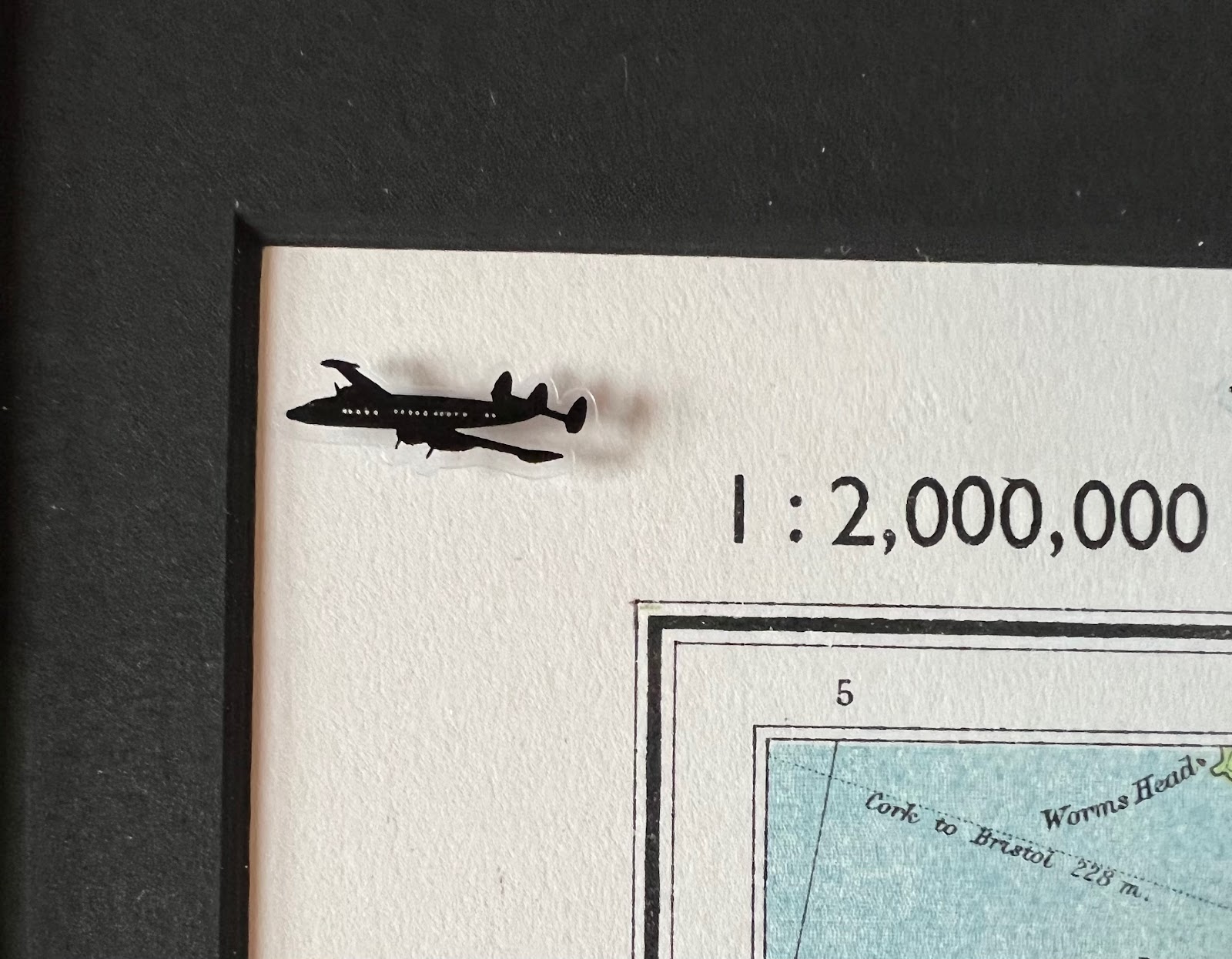

So, I started looking for stickers. But I couldn't find what I wanted. So I asked some friends on Ravelry, and someone suggested looking on Etsy for "planner stickers." Evidently people treat their planners a bit like scrapbooks and use fun stickers to categorize things. Huh. Who knew?

I ordered from several different vendors (at less than $3 per sheet, they were far more reasonably priced than what I could get at craft stores), but the ones I liked best were from

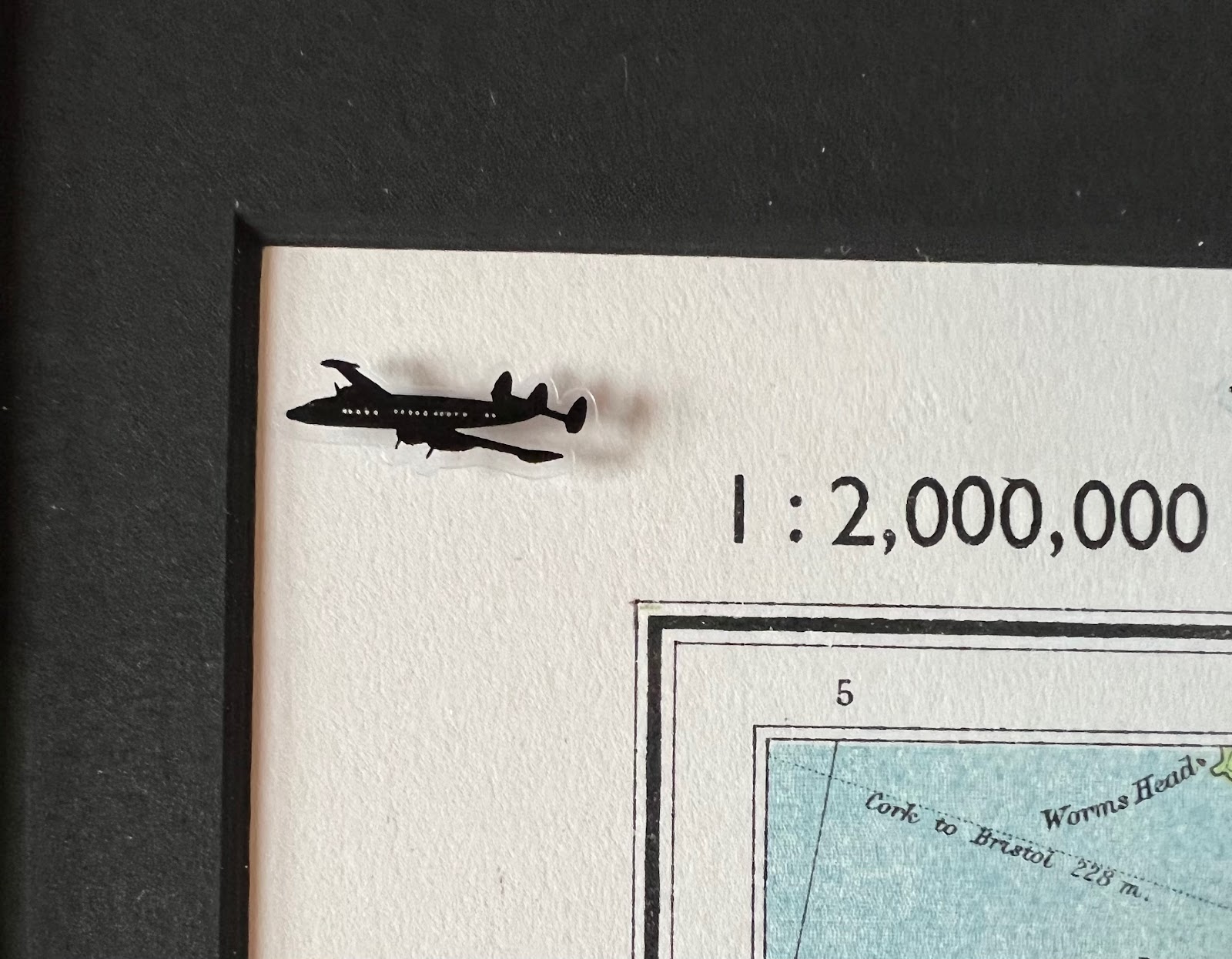

OKPLANS. Her stickers were a very deep black printed on a clear sheet, and they have the right amount of simplicity, and the right size. And when some of the stickers from other vendors arrived and didn't look right at all (my first taxi sticker was barely a charcoal gray and didn't show up against the map well at all, and some stickers were printed on white paper which looked funny), I asked her to do some custom work and she did a great job, creating a vintage taxi and a vintage airplane with propellers and a triple-tail based on an actual Lockheed Constellation, which is the kind of plane my grandparents flew to America in. So, a HUGE shout out to Kimberly for her excellent sticker-design skills. And she didn't even charge me the custom work - I just paid for a normal sheet of stickers, and now she offers the designs I requested for sale in her store to anyone who wants them.

Also, because the stickers are on the glass, you can see UNDER them and still read the map, by moving to the side a little. Very nice unintended and 3-D effect.

So, here are a few closeups (click on the images to enlarge):

Orange Dots (first escape to France):

|

| Taxi from Brussels to Pas-de-Calais, May-June 1940. |

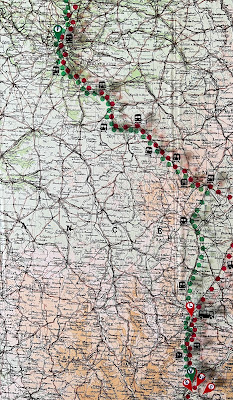

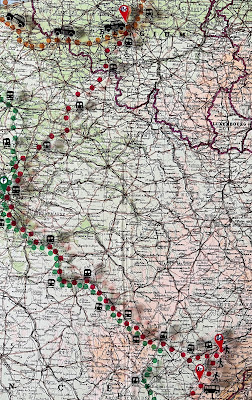

Red Dots (Second escape to France):

|

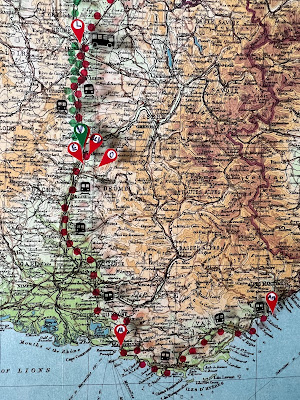

Pano that shows the entire trip from Brussels to Antibes,

fall, 1941. Smaller sections shown below. |

|

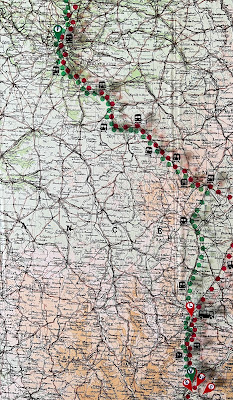

Train from Brussels to Besançon, fall 1941.

Route is a guess, and follows escape lines.

|

|

On foot from Besançon through Arbois,

bus from Poligny to Lyon, fall 1941. |

|

Train from Lyon to Antibes,

then back up to Valence, fall 1941.

|

|

Valence, Beaumont-lès-Valence, Étoile, Ourches. 1941-1947

Note the mountainous region off to the right - that's the Vercors massif.

|

Green Dots (Immigration to America): |

| Train from Valence to Paris, January 1947. |

|

Train from Paris to Calais,

ferry across the English Channel,

train to London, February 1947.

|

|

| Plane from London to the NYC, February 1947. |

|

Lockheed Constellation!

Four propellor engines and a triple tail. |