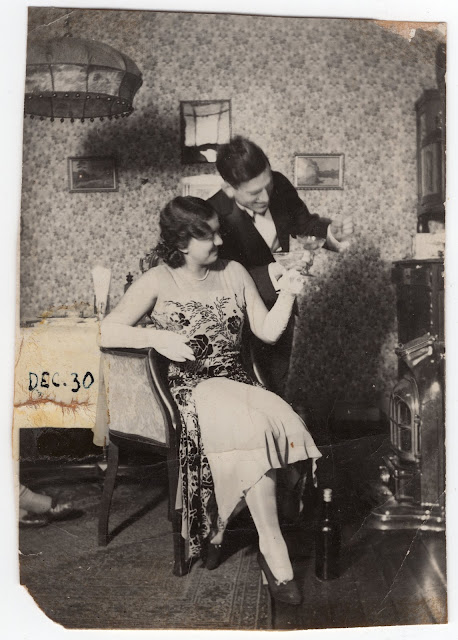

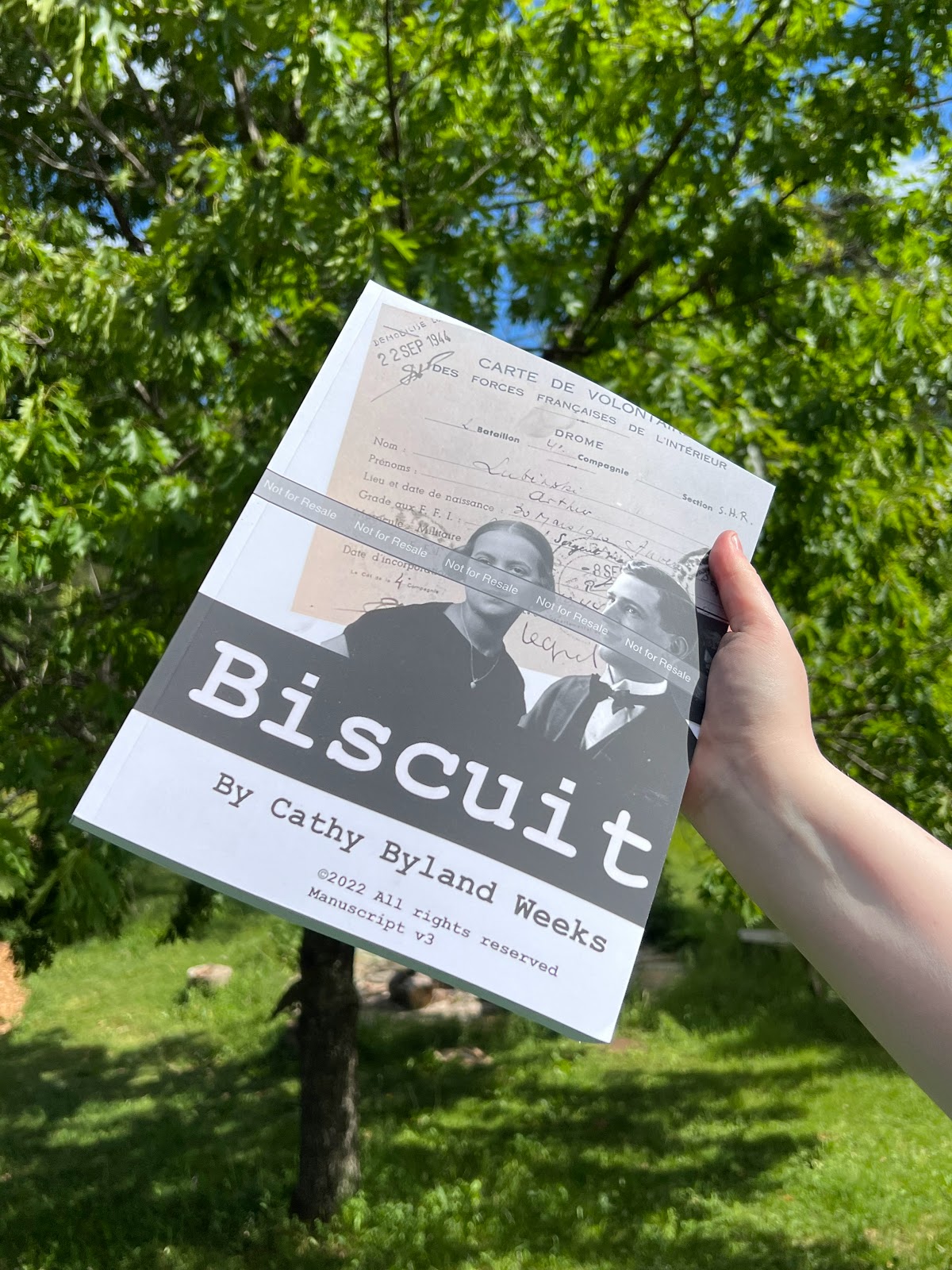

Ok, so my grandfather didn't talk much about the submachine gun he used in the maquis; he only said that it was a Sten and not very good, and that he'd heard that the American-made Thompson (aka"Tommy Gun") was pretty good. That's about all I know directly from him.

As I researched what life in the maquis was like, I realized that I needed to write about my grandfather learning how to use it. So, I researched how they trained on the weapon given that they a) didn't have enough to go around, and often passed one gun from unit to unit for training purposes, b) in the absence of adequate supplies of ammunition, they learned to assemble and disassemble the weapon in record times.

As I wrote the scene below, I had to balance two things: the character's experience and perspective, and the author's experience and perspective. Now, my perspective should be entirely absent. It should be all about my grandfather and who he was, but some of myself may have slipped in.

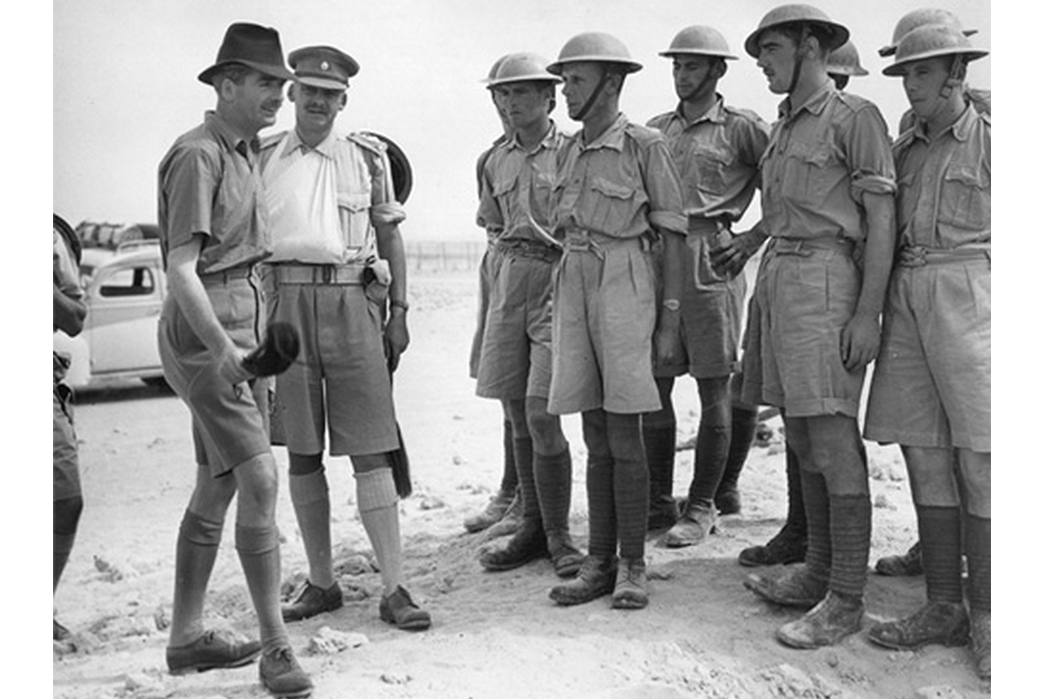

So let me describe the relevant parts of my grandfather's personality: he wasn't a pacifist, but he was also very ... peaceable and non-violent. He spent most of WW2 avoiding war zones and escaping to safer places, so he could protect his family. He also never served in the army, so had zero combat training. But in the maquis, he DID learn to use a Sten. And as an engineer, he was also very curious about how things worked. But, I don't believe he ever owned a gun, even after living in Oklahoma (where the Second Amendment is sacrosanct) for 40 years. Even after surviving the Holocaust.

[Correction: I now have reason to believe he did serve in the military - in Belgium, all men served mandatory military training after high school or college]

Now for my background: I too am not a pacifist, but I am also pretty strongly anti-war under most circumstances. And while I've fired a gun a few times in my life, I am very inexperienced. I've never held a submachine gun (or even seen one except in the movies) and know little about how they work or what they are like. I am only a couple of baby steps above novice.

Now what that means is that in order to write about the Sten in an - ahem - authoritative way, I researched the hell out of them. To my surprise, there is a group of people who really like firing and teaching about antique firearms, so there were lots of youtube videos for me to watch. I also found animations that showed how to disassemble and reassemble it, both into the four main parts, but also all the way down to the 50-ish individual components. I watched videos of a man reviewing what it was like (how awkward it was) and firing it at a range to demonstrate its accuracy and he showed how the 4 main parts went together. I read lots and lots of stuff, too, and pestered a friend when I couldn't find certain details (like how to switch it between automatic and single-shot mode, or whether it was a centerfire or rimfire weapon). I even read the f-ing manual for heaven's sake (people have scanned the WW2-era paper manuals and put them online). Ok, I only skimmed the manual. It's hard to absorb the info without the actual item in your hands.

Anyway, I wrote a scene describing how Grandpa learned to use it. But ... it might reflect my own curiosity and I might have over-compensated for my ignorance, and I might have gone into too much detail. Will readers be curious about what it's like to fire an obsolete, cheap, poorly-made, mass-produced submachine gun? Or does it drag? Does it allow you as the reader to experience Grandpa's gun-ignorance and reluctant-yet-curious personality? I'd love any feedback you might have.

As he was putting the casing back on the radio, he felt a tap on his shoulder.

It was Lucien. “Biscuit, you need to learn the Sten. Only one other person besides you hasn’t, and it should go to the next unit soon.”

Arthur sighed. “All right. Let me finish this.” He tightened the screws that held on the metal casing. “I am ready.”

Lucien led him to the worktable where more than a hundred men had learned the Sten. First, he taught Arthur the names of all the parts and how to assemble and disassemble the gun. “We don’t need to strip it down to the individual pieces. Only down to the four main ones.” Lucien picked up the main part of the gun. “Receiver assembly.” He then grabbed a thin tube protruding about 7 centimeters from a wider tube. “Barrel screws into the front of the receiver assembly.” He quickly hand-twisted the barrel into place. “Butt stock.” He picked up the stock, which had a locking mechanism on one end, lined it up with the other end of the receiver assembly, and slid it upwards until a small button clicked into place. Lucien picked up the magazine. “This one last.” He clicked it into the side of the receiver assembly.

Within a short time, Arthur could put it together and take it apart, if not quickly, then at least correctly, and he could do it from memory and without coaching.

Then Lucien taught Arthur to use the selector button a little forward of the trigger. “Push the side marked A to put it in fully automatic mode. Push the side marked R to take single shots.”

“What does the R stand for?” Arthur asked.

“Repetition.” Lucien shrugged. “It makes no sense. But you use it when you want to take single shots.” Then he pointed to the magazine protruding from the left side of the gun. “It attaches on the side instead of underneath, so you can crawl without catching the magazine on the ground.”

Finally, Lucien taught him to “safe the gun” by locking the charging handle into a slot at the top. If he dropped a safed Sten while it was loaded, it could not accidentally fire.

“And now, let’s learn to use it.” Lucien showed Arthur how to use the sights to aim and how he had to use his left hand to cradle not grasp, the underside of the barrel shroud. It was hard to brace the weapon — it had no real grip for the right hand when pulling the trigger and every good spot to grab the gun with the left hand caused problems. Not the magazine because it wiggled slightly, and the play caused the bullets to misfeed. Not the barrel, which got hot, and not the barrel sleeve because that obscured the weapon’s sights. So the only way to brace it with the left hand was to cradle (but not grab) the barrel sleeve from below. It was an awkward weapon to use.

“Also, don’t dry fire the gun,” Lucien said.

“What is that?” Arthur asked.

“Don’t pull the trigger with no ammo in it.”

“Why not?”

“Because it could damage the firing pin,” Lucien told him. “I’m not sure it’s true because it’s a centerfire weapon — the firing pin doesn’t strike anything when it’s not loaded. But it’s a cheap weapon, so who knows?”

Arthur practiced firing the gun by pointing it at a target and pretending to pull the trigger while Lucien placed his fist under the barrel and smacked it upward repeatedly as fast as he could while Arthur tried to hold it steady.

“Firing with live ammunition is pretty different,” Lucien said. “In automatic mode, the kick will be much faster than we can simulate — but this was the best we could come up with,” he said. “Now, it’s your turn to teach the last person.”

“Me?”

“Yes. Captain Sanglier says the best way to reinforce what you’ve learned is to teach someone else.”