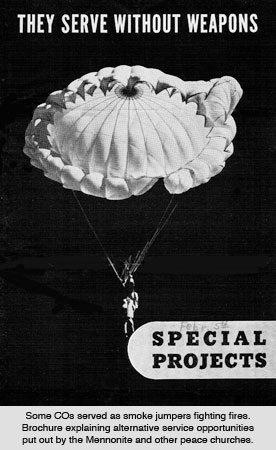

|

| Some conscientious objectors WERE trained how to parachute, but for stateside service: Smoke jumpers (aka forest firefighters) |

The main source of information for Biscuit is the oral testimony I recorded in 1988 when Grandpa Arthur was 78 years old. He was slowing down quite a bit by then, but mentally, he was still quite sharp.

I've managed to confirm quite a few of his stories, and when I compare his stories to earlier primary sources, his stories have remained consistent over the years. He was also personally extremely honest, so it's safe to say he was a very reliable witness.

However, he was not infallible. No one is. In something like 15,000 words of primary sources, I've independently verified many of his stories, and only confirmed two minor mistakes:

- The date of his landlady's murder (he was off by 3-ish weeks).

- The size or form-factor of the tank traps his factory produced prior the invasion of western Europe in May of 1940 (his description doesn't match any tank-trap that I can find).

There are probably other minor errors, but my research has shown that he mostly got stuff right.

But what do you do, when an absolutely pivotal story, perhaps THE most important one in the whole book might not be entirely correct?

Through the efforts of some friends, I've discovered that he may have gotten some combination of details wrong about the first American he ever met:

In August of 1944, during the heavy fighting that followed D-Day, my grandfather (who was serving in the FFI/French Resistance) met an American conscientious objector (CO). That in itself isn't all that unusual - by the end of WW2, there were more than 40,000 non-combatants serving in the US Military.

Anyway, Grandpa had heard about the Thompson submachine guns that he thought everyone in the US military carried. He asked the young American if he could see the man's Tommy gun, and to Arthur's shock, the man stated that he didn't carry any weapons at all, that his religion forbade the taking of a life. Grandpa thought the man was crazy (but courageous), and admired his moral stance, even if he himself didn't subscribe to it.

It's funny because this story is one I grew up hearing, and so I never thought to question it. And for the scene in the book, I don't have to rely only family lore or my memory, as he wrote about it twice and also mentioned it in his oral testimony which I recorded in 1988. If you are interested, I've quoted his actual words at the end of this article. They are really quite powerful.

But, as it turns out, my Grandpa's CO was exceptional to the point of seeming unrealistic:

- He was a paratrooper.

- He was a radio operator.

- He was part of a 15-person commando unit

- He brought an enormous transmitter to France that apparently allowed him to talk to the pentagon in Washington DC (from France!).

But, two of my beta-readers who are knowledgeable about history were tripped up by the CO story, because:

- Conscientious objectors who joined the military overwhelmingly served as medics and chaplains.

- It doesn't make sense to send a non-combatant as part of such a small team, where every person's ability to fight counts.

- Radio transmitters that were at all portable didn't have the range to send intelligible singles across the Atlantic. Here's one that was in use: SCR-299. It's maximum range was 2300 miles, about 1700 miles short of being able to talk to Washington DC from southern France. And parachuting one in seems unlikely; they would likely have been boxes of broken glass by the time they reached the ground. These radios had their own generators and were normally housed in the back of trucks. Sending such a unit seems unrealistic for a parachuted team with no expectation of transportation.

- The SCR-499 was a better candidate - it was basically the same radio as the SCR-299, but was hardened for airborne use and was modular, so it could be assembled once the paratroopers got themselves and the radio to safety. It only had a range of about 100 miles but I suspect that it would have been possible to bring along a better antenna.

|

| The SCR-299 had a range of 2300 miles, not the 4000 miles between Valence France and Washington, DC. And the size isn't conducive to a parachute drop |

As my beta-readers pointed out, truth is sometimes stranger than fiction, and just because we can't prove or disprove the CO's details, doesn't mean it didn't happen. Besides, it was wartime, and sometimes the Allies did crazy and seemingly illogical things when they had to. Maybe a greater percentage of small units survived if they took a medic along? Maybe the guy was actually a medic and only the backup radio operator, and the main one was killed before he reached the ground?

I do believe my grandfather met and was inspired by an American CO -- that part isn't in question. But there is some chance he conflated two events into one, though I doubt it. I just wish I better understood how it came to be.

As for the radio, I suspect that either the American was pulling my grandfather's leg about being able to talk to the Pentagon, he was speaking metaphorically OR my grandfather misunderstood (he did speak English but not-quite-fluently by that point, and Grandpa did say he had difficulty understanding the American's accent.

[Added: It turns out the SCR 299/499 probably COULD talk directly to the eastern seaboard of the US, depending on time of day, antenna, and atmospheric conditions, using techniques like bouncing the signal off the ionsophere]

I've written to the U.S. Army Center of Military History to ask about the CO and the transmitter to see what they can tell me. I'll get back to you, if they reply.

Anyway, here's how he described it:

1974 Yellow Pad Stories:

I kept on going and did find them. But I have not been the first FFI to contact them. They were with another company of FFI, whose patrol stopped me at gunpoint. A minute later I have been in their camp. All the Americans were asleep except one, busy with a huge and heavy trunk-like box.

“What is this?” I asked in English.

“A radio transmitter” answered a tall and handsome soldier with a strange accent, which I could hardly understand.

“Show me your weapons,” I asked.

“I don’t have any,” he answered. I could not grasp “Parachuted/behind the enemy lines, in mountains infested by them, without any weapons; did I understand you properly.”

“Yes Sir” he said. “I am a conscience objector and I volunteered to be parachuted as a radio operator to prove once for ever that my objection to bear arms is not due to cowardice but to my belief.” He seemed so strange, so great to me, the first man of the land which will become my country in the future.

In Belgium and France, the freedom of an individual to think, believe and say whatever he wishes is the utmost, but in it disappears in war time and the fact that conscience objector to [not] bear arm may be respected in wartime seemed unbelievable to me.

Feb 1988 engineering award speech:

Then suddenly and unexpectedly Germans left our mountains in a hurry. The reason was that they have detected the fleet of the secondary landing approaching the Mediterranean Coast.Then came an electrifying news, An American commando was parachuted somewhere in our mountains.I was ordered to search for them and to contact them. Here I was hiking at night, from valley to another valley, from a high pass to another high pass. I met a shepherd on a high pasture.“Have you seen some Americans here?”, I asked. He said "no, but 5 minutes ago Germans were here.”I kept going and finally joined the American commando of 13 people. They had a radio transmitter, as I remember, maybe 6 ft. by 4ft. by 4ft. It was huge, as this was a long time before transistors, printing circuits and chips. But they could talk to the Pentagon in Washington.I reported that I was supposed to contact the commanding officer. They told me to wait. By the way, I was only a sergeant.Then I started to talk to a soldier, a tall, handsome boy. I asked, please show me your Thompson submachine gun. Mine was a British made, Sten.He answered, “I do not have any. As a matter of fact I have no weapons at all.”“Why?”, I asked.“Because my religion does not allow me. I am a conscientious objector.”“But, hell, what are you doing here, beyond the enemy lines, without weapons? Your odds of survival are very, very slim.”“Yes,” he answered, “I know. But I wanted to show that I am a true conscientious objector, not a coward.”I looked with great admiration at this first American I ever met.No less was my respect for America, my future country, in which the religious freedom extended to conscientious objectors.

May 1988 Oral testimony:

You read my speech in Dallas. It was not exactly correct, because I say that the first American I ever met was the radio operator – conscientious objector.

I already met – I already saw at least, didn’t meet him, didn’t talk with him, a parachuted team of one American officer, one British officer and one French noncommissioned officer, who spoke as a translator. They came to Ourches, and I remember, they were thirsty so they were given water and the English and French drank this water, but the American took a pill dissolved in the water before drinking to avoid contamination. Well, that’s very normal for Americans – I am American now – to behave that way. But in France at that time, everyone laughed like hell. “What’s the matter them? Why are they different?”

Well, in any event I saw them, but the one whom I talked freely was only the guide about which I talked on my Dallas acceptance speech of the ... which you know the story.

According to family lore, after my family immigrated here in 1947, Grandpa tried to find the man, but was unsuccessful. I also wish I knew the American's name, but that may be lost to history.

Note: There's a part II to this article.

|

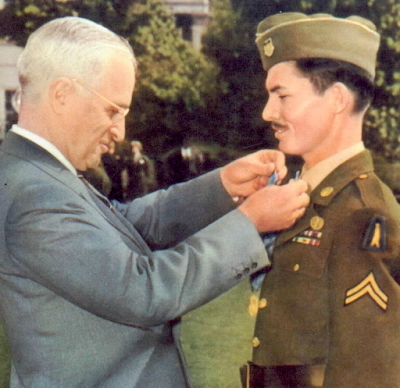

| Perhaps the most famous CO: Desmond Doss receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1945 from President Harry S. Truman for saving the lives of over 70 wounded men during WW2. |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Neither spam nor mean comments are allowed. I'm the sole judge of what constitutes either one, and any comment that I consider mean or spammy will be deleted without warning or response.