|

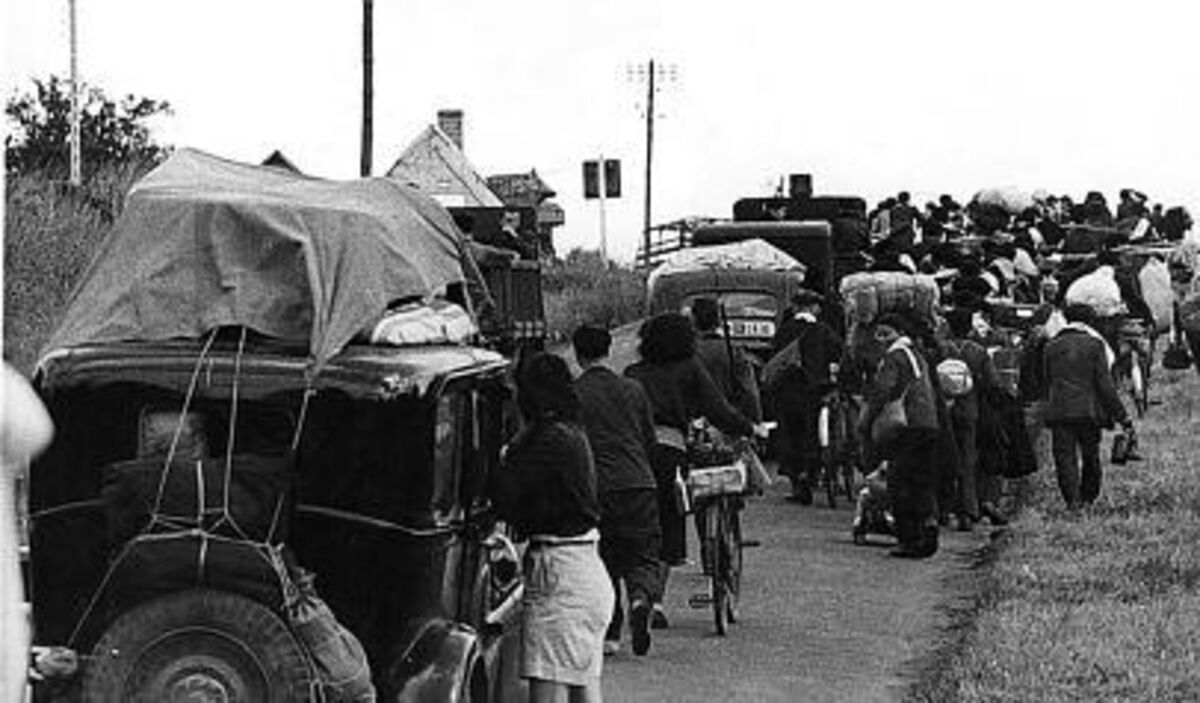

| French refugees on the road of the Exodus, 19 June 1940, near Gien, France. CC-BY-SA 3.0. This photo was taken by a German soldier. |

Between May 10, 1940 when the Germans invaded western Europe, and the end of June, when France surrendered, a massive migration, one so biblically enormous, it was given the name l'Exode (the Exodus) in France.

The 8-12 million affected people were a mixture of refugees from Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands, but also internally displaced persons (IDP) from within France itself, and they all had the same goal: to get farther from the front, to find safety.

Regardless of nationality, people sort themselves into three groups in tense situations: 1) the exceptionally good people who rise above the situation and try to help those around them; 2) the genuinely bad people who heartlessly take advantage of the desperation of others; and 3) everyone else, the desperate masses who just do what they can to survive. This last group is massive, usually comprising over 90% of the participants.

It's hard to capture what the Exodus in 1940 was like, and hell, it's hard to even imagine it. Millions of people were on the road, stuck in a traffic jam from hell that lasted not hours, but weeks. People were on foot, on bicycles, in horse-drawn carts, or in automobiles. But mostly, they were on foot. The average speed was 1-3 miles (2-5 km) per hour.

There was a heatwave, and there wasn't enough food, water, or fuel. There were no sleeping arrangements, showers, or even toilets. People were packed closely together with their dogs and horses, and surrounded by clouds of automobile exhaust. The smells must have been intense.

There were constant threats of crime, violence, and chaos. People were beaten for their food. Women were raped. Children were occasionally separated from their parents (sometimes permanently), and war profiteers charged people exorbitant fees for sips of water, and a simple sandwich might cost a week's wages.

And the Luftwaffe and their dreaded Stuka dive bombers made a habit of not just strafing Allied soldiers, but columns of refugees as well. There are a couple of scenes in the 2017 movie Dunkirk that show what it was like:

Note: that weird high-pitched whining sound that sounds like an anvil dropping on Wile E. Coyote's head (link to short clip that includes the sound) wasn't an air-raid siren, nor was it an artifact of the Stuka engine noise. Rather it was psychological warfare in the form of ram-air sirens mounted on the Stukas themselves. They were called "Lärmgerät" (noise devices) but despite popular myth, they were not really called "Jericho Trumpets" (which is what I think the whistles on bombs were called). Most common was probably "Stuka Siren".

My grandparents and great-grandparents joined the Exodus of 1940. And they did it with my newborn Aunt Lilly, my grandmother, who wasn't producing enough milk (probably due to terror and the deprivations of the trip itself), and my great-grandmother, who suffered from tuberculosis. My grandfather told me about the taxi he hired (but not how they avoided running out of fuel), about the traffic jam, but not how long they were on the road, about who he took with him, but not about their misery. He summed up the experience in a single word: pathetic. I think he was describing not just the stasis of the troops, but how he and his family felt.

So after Lillian was born, and as soon as we could move – I didn’t have any car at the time, so I rented a taxi cab – and in the taxi cab, big taxi cab: Roma and myself and the baby Lillian, a few days old, and my father and my mother, and Felicie who was like family, and in addition the cab driver and his wife and a child, were all squeezed in one big taxi cab. We started escaping from Brussels.

Well, you couldn’t do more than ten miles a day at most, because the highway was crowded and millions of people who remembered the war – the first World War, 1914 to 18 ... So they wanted to escape and be on part of France where the front would never arrive. So millions of them were moving; including fire trucks with people on it. And including ambulances with people on it; etcetera, etcetera. Completely packed by millions of people. And English and French and Belgian troops couldn’t move because of the civilians packing the highways.

It was pathetic.

--Arthur Lubinski, Oral Testimony, 1988

|

| Source: https://www.odomez.fr/ Note the mixture of cars, bikes, and pedestrians |

When I recorded him, Grandpa said they traveled ten miles (16 km) a day, and the route I think they took (which is admittedly a guess), from Brussels to the coast, and then along the coast to Montreuil-sur-Mer, France, taking them right past Dunkirk and Calais, was 180 miles (290 km). I think they also hoped to reach England, so a coastal route made sense. He also said:

And we arrived at the North Sea. In the … you would say “state.” In French, it is département, department – but that means state if you want – of Pas-de-Calais on the English Channel.

The North Sea comment also suggests a coastal route. I'm not certain if they stopped in the city of Calais or just the region of Pas-de-Calais, but in 1988, I got the impression he meant both, although I'm not entirely sure.

|

| The route my grandparents might have followed during the Exodus of 1940 Interactive Google Maps Link |

(Added: I now think they probably went to Lille first, then north to Calais)

My research suggests that a key route during the Exodus was from Brussels to Lille in France, and from there to Paris and then to Bordeaux. But we know they went to Pas-de-Calais, and Paris and Bordeaux were in the wrong direction for that. It's possible they went to Lille first, and then turned north, but that route and the stops they must have made (they stopped every night in a town with a maternity clinic for my grandmother's benefit), and that would have added a day or two to the trip. So, I think they made a beeline for the coast.

Another problem is that if they traveled only 10 miles a day, then the dates don't work - it would have taken them 18 days to arrive in Montreuil, where they stopped for several weeks (a dairy farmer took them in). However, at 10 mpd, they would have encountered many of the areas after they had fallen to the Germans, whereas his story as a whole suggests that they encountered German soldiers only at the end of the trip.

So, I started researching the Exodus to see how far people typically traveled in a day:

- On foot: 6-12 miles per day (10-20 km). This was the majority of the refugees.

- Bicycle or horse-drawn cart: 12-18 miles per day (20-30 km)

- Car: Up to 20 miles per day (32 km). Autos were less common, there were serious fuel shortages to contend with, and many cars were abandoned after they ran out of gasoline.

I also have the sense that the trip took less than 2 weeks, probably about 10 days, based on their departure date (May 15), the length of time they spent in Montreuil (3 weeks), and the approximate date they returned to Brussels (after the cease-fire went into effect in France on June 25, 1940). In those days, cars traveled nearly as quickly as they do today, and under normal conditions, they would have made that drive in about 3 hours.

The return journey to Brussels would have been tremendously easier. The roads had mostly cleared by then, and the French government offered fuel vouchers with short expiration dates to encourage people to fill their gas tanks as soon as possible and go back to where they came from.

Well, after three weeks France capitulated. There was no reason for going farther south. So we went back to Brussels, and found our beautiful apartment in town.

Bibliography:

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exode_de_1940_en_France (in French, but if you set your browser to translate, it's a good read).

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Exodus_(1940)

- https://webdoc.france24.com/exodus-france-german-invasion-war-1940/

- https://www.france24.com/en/20200304-eighty-years-after-millions-fled-the-german-army-revisiting-the-paris-exodus

- https://www.landofmemory.eu/en/sujets-thematiques/the-exodus-of-1940/